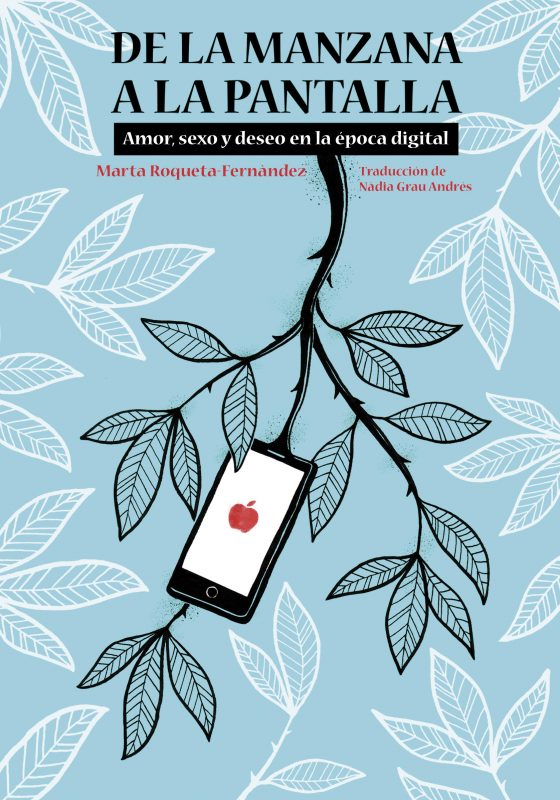

Marta Roqueta Fernández is a journalist and feminist, a path that has led her to investigate the representations of gender, ethnicity, functional diversity and LGBTI identities in mass culture. His first book From the Apple to the Screen (Pagès Editors, 2019) published last October, has already expired its first edition.

Media analysis is our common line of work . So we talk to her about this essay where she reflects, from her own life and experience, on the influence of the digital world on our lives.

The novelty is that the book can also be a roadmap for professionals in the world of education. He carries a didactic guide to work with young people, as he explains in this interview.

Fr.- What motivated you to write a book on sexuality for young people and adolescents, when it seems that they have learned everything?

The book is part of a collection called Nandibú-Zeta, from Pagès Editors, and the idea was to analyse the current situation and how these issues are influenced by the digital world. The first theme was love, sex and desire. So I was very interested in exploring how the digital world shapes our way of loving, desiring and having sexual relationships, and how it strengthens, and at the same time unchallenges, all the regimes of power articulated around love, sex and desire. That was my idea. But, it turns out that young people do not have a sex education as one would expect, that is, an education that goes beyond the prevention of diseases, and focuses more on issues such as affection, desires… The idea was to take advantage of the analysis of the connection between the digital world and sexuality to address issues related to sex education, which seem to be clear, but at the time, you analyze it and in practice are not so clear.

eP.- You have counted on testimonies of young people to write your essay. Cómo se configura todo esto dentro del libro?

MRF.- In the book I explain my experiences, examples of mass culture, and I relate it to the feminist, LGBTI and antiracist theory of the moment. And although they do not appear, it is true that to finish knowing what experiences in my life could be relevant, I do a series of interviews with young people to see how I could help them and how I had to focus on these issues. I talked to young people to find out if what I proposed was relevant, if I had left something that particularly worried them and to see how my testimony could help them solve their doubts.

eP.- Now you go to high school to do book training. How is the state of the matter? Is ignorance so great?

MRF.- I have done a couple of trainings in Institutes and I have noticed that in general students have the theory very learned, in some way, but when you give examples, in practice, where doubts, contradictions, etc. arise. It is true that in my book I not only explain love from a Western point of view, but from there I use LGBTI examples or around the world; from Japan to Sudan, or to Cuba; of artists who have challenged the sexual regimes of their countries. Because, here you go racialized students, from here, Muslim girls who have doubts, talk, ask for information and feel represented by these examples. Because what has happened is that in the West we have a very specific idea of romantic love, which is used to consolidate a heterosexual, monogamous, father, mother and child family model, and in accordance with capitalist society and the sexual division of work. What I do in the book is to give other examples of ways of understanding love, forms of resistance to colonial imaginaries about sex and love, or about some countries such as Japan, which is a mixture of the taboos that exist in that society. There are students who do not feel represented in conversations about love, sex and desire, but who, with the book, have an easier time expressing according to what attitudes and according to their concerns.

It seems that girls have been more receptive and participative. What happens to the boys in the formations or when they read the book?

MRF.- I conceived it as a book for people of all ethnicities and all genders: boys, girls, non-binary people, cis, trans, etc. And in this sense, it is true that racialized people, and especially girls, also white girls, and LGBTI people, racialized or not, have reacted favorably to the book. In the case of white, straight and cis boys, there is more reluctance. I believe it happens because, whether you like it or not, machismo and LGBTIPHOBIA are ways of seeing ourselves and seeing others. And many times these forms of relationship, sexist or LGBTIPHOBIC, have been presented to us as an appropriate way of relating to others. And I think that two things happen to children: a certain disorientation, that is, at the moment we question all these gender issues, because they do not know how to act, they do not know who they are, and the moment they question how to act with others, they do not know how to act either. The straight white boy, so to speak, as an example, is harder to get in. But, in any way, I already knew that this would happen with the book, and then I looked for examples so that children can feel identified, and that they can understand where this discomfort comes from when they deal with these issues and, above all, what they can do with this discomfort and how they can act to have more egalitarian relationships. but at the same time, healthier for them. Because deep down, machismo affects the way they perceive themselves and sometimes affects them in a negative way.

eP.- Is the book also aimed at teachers? How have they received it?

MRF.- Although the book was originally intended primarily for young people, we have seen that during the time it has been on sale it has also interested adults. In fact, when you think of content for young people, you know that sooner or later an adult will read it. Among the teachers it has been very well received, also among public institutions and the adult public in general. It is true that there have been some cases in which, for example, there is a teacher who does not want the book to be talked about in her educational center, because she said that, as we talked about LGBTI theory, theory queer, because the theory queer She was not a feminist and therefore this book did not interest her because she was not a feminist. When queer theory really has feminist aspects, and in any case queer theory and feminist theory do not have to be absolutely opposed, nor one is in conflict with the other.

eP.- Has the influence of the media been so bad in our way of loving, desiring and having sexual relations?

MRF.- My book is based on the idea that digital technologies and the audiovisual world are not in themselves bad, but that, in any case, what determines that they are harmful or beneficial is the use made of them. And the book is full of examples of positive representations of sexuality and the ways of loving that we find in the audiovisual world. From POSE to Steven Universe or FROZEN, Disney. I also quote artists such as Alaa Satir, Megumi Igarashi. All these artists approach us to new ways of seeing sexuality and relating to other people. The idea of the book is this: so far we have had a very apocalyptic image of the relationship between digital technology, love, sex and desire, but this is not necessarily the case. On the contrary, the diversity of voices facilitated by the digital world also leads us to discover new forms of love that, until now, were covered, because those who had control of the audiovisual media were a few hands. And he also creates digital spaces in which new ways of loving can be developed.