- PUBLISHED BY Alfredo Cohen Montoya

In 1993 the Colombian national football team played against Argentina and Faustino Asprilla, one of my idols, walked the field on the right side like a gazelle trying to get rid of all the opponents to finally fall scattered on the grass.

“Sondeputy… Black you had to be!” “Oh,” cried I, then, without a belly of embarrassment.

In this fourth column for EL COMEJÉN I want to talk about racism; since with elParlante I have been doing workshops for more than 10 years in institutes where cultural diversity is residual and, therefore, young people have hundreds of prejudices and stereotypes about migrants. When I am in these classes I tell them my personal story to tell that of others who, like me, have come to live in Barcelona with the intention of having a better life.

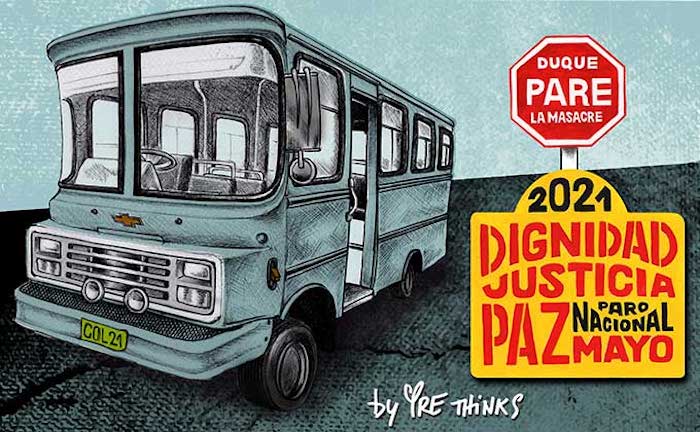

I understood a long time ago that it is impossible for these guys and girls to put themselves in my shoes. Never, no matter how sensitive they are, no matter how hard they try, will they have the nightmares I had this week. None will feel in their flesh the feeling of having family and friends in danger, 8,000 miles away. I will not get them to feel the frustration and sadness that invades me to see that Colombia continues to murder itself, in an endless vicious cycle of hatred and destruction.

This week, the only country I suffer for at a World Cup burst in my face. Yesterday, watching “El olvido que seremos” at the cinema, I cried again. No one will be able to put on their shoes. Neither my Facebook contacts, nor my Catalan friends, nor my family, nor my partner, nor the teenagers of Sarrià.

The pain of others cannot be felt as one’s own, each pain is particular, inalienable, non-transferable and therefore should be respected, without judgment, without attacks. Marshall Rosenberg points out that communication, if it is empathetic, if not violent, has the ability to observe, listen, attend to the emotions of the other and accompany them. Understanding emotions as responses to deep needs is the only thing that can help us empathize with others.

Understanding is not feeling, but it is better than nothing. If I don’t judge the other’s pain, I can understand the anger of Sandra, an old friend of my Facebook, whose hairdresser was destroyed by angry young people during the protests. The business I had built hard for the past 10 years, like me. Also, although I am very wrong, I can understand the fear of Marcela, the bank cashier who felt that what they were destroying some hoodies was also hers. It costs me, it hurts, I find it absurd, but with effort, I can understand that a small part of the country is afraid of losing its few or many privileges, because it also happens in less unequal societies, such as the one I live in.

But just as I can understand Sandra and Paola, I can do it very especially with the hundreds of thousands of young people and adults who have come out to parks, squares and streets despite Covid-19. I can perfectly understand the peasants and indigenous people who, fed up with starvation and violence for centuries, have blocked roads and toppled statues of European colonizers.

How can we not understand that the usual outcasts will one day get tired? I can perfectly understand that a youth with nothing to lose is willing to take the protest to its last consequences.

However, I cannot understand the police shooting him in the village as I cannot understand to whom he gives this order. I cannot even imagine the pain of mothers who have lost their children in these demonstrations and in the endless Colombian wars. Those who lose their parents are called orphans, those who lose their children have no name.

I refuse to accept that a life is worth the same as an office, a car, a cell phone, but I understand that violence is a sad way of expressing pain. The pain of Colombians is the product of endless unresolved needs by a state that has opposed the majority having opportunities to please very few.

To transform the country, we will have to lose our fear. But not only to go out into the street to express our pain, but also to listen to the other’s, to welcome them, to understand them, to understand where they come from to try to feel it as our own, although we will never succeed. Building peace is very difficult, but building war is always worse.

Faustino “El Tino” Asprilla rose from the ground as if he had heard me, took two or three Argentines out of the middle and nailed the ball into Goycochea’s right corner. What was serious was not that I, a 9-year-old boy, sought affection and admiration, the most painful thing was that the adults next to me celebrated with applause and laughter, that racist and classist way of becoming a man, of little Alfred Trump.

Text originally published in EL COMEJÉN.